Islamic Philosophy as a Compass of Meaning in the Era of Science and Technology

Explores perspective on the relevance of Islamic philosophy amid the dominance of science and technology. Islamic philosophy is presented as a compass of meaning that enables students to integrate rational inquiry, spirituality, and ethical orientation while confronting the modern crisis of meaning.

KNOWLEDGE PRODUCTION

Siti Asma Ahmad (Al Hikmah Institute Felow)

1/19/2026

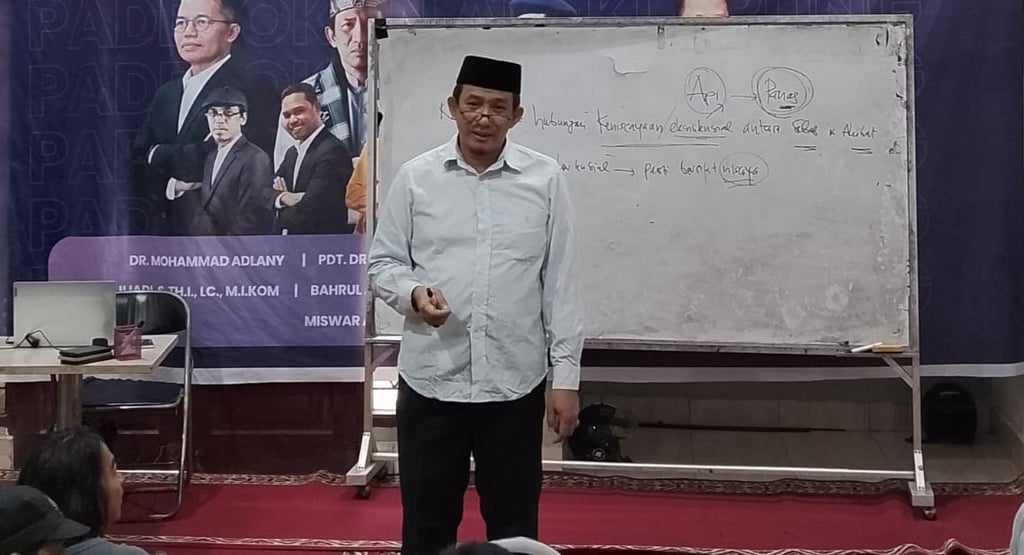

Amid the growing dominance of science and technology that continues to accelerate modern life, Islamic philosophy is considered to retain a crucial role in the academic world, particularly for university students. This view was expressed by Mohammad Adlany, a lecturer on Islamic philosophy at the Short Course Padepokan Aufklärung VI organized by the Al Hikmah Institute Makassar.

In addition to being actively involved as a lecturer at Al Hikmah Institute Makassar, Adlany is widely known as a scholar of Islamic philosophy, a book author, and a speaker at various forums on philosophy and Islamic thought. In an interview conducted on the sidelines of the short course on Monday, January 19, 2026, with Siti Asma Ahmad from the Al Hikmah Institute team, he highlighted the urgency, relevance, and challenges of teaching Islamic philosophy to today’s students.

According to Adlany, the urgency of Islamic philosophy lies in its function as a reflective and critical foundation for science and technology. He emphasized that while science is capable of answering questions about how, it is insufficient to address questions of why and for what purpose.

Islamic philosophy—particularly through metaphysical studies encompassing ontology, cosmology, epistemology, psychology, theology, and ethics—helps students recognize the ontological and epistemological limits of science. This awareness is essential to prevent students from falling into scientism, while also providing value orientation and purpose in the use of technology.

“In this sense, Islamic philosophy functions as a compass of meaning amid technological acceleration,” he stated.

Adlany rejected the assumption that philosophy stands in opposition to spirituality. Within the tradition of Islamic philosophy, he explained, there is no dichotomy between reason and faith. Reason is positioned as an instrument for uncovering truth, not as an adversary to revelation.

Revelation requires reason in the process of rationalization, while revelation also offers material for contemplation by reason regarding the vastness of reality. Intellectual criticism is directed toward the purification of understanding, not the destruction of faith. Spirituality, in his view, is not an anti-rational attitude but an existential depth born of rational reflection.

“This is what distinguishes critical thinking in Islamic philosophy from nihilistic skepticism,” he explained.

Furthermore, Adlany emphasized that Islamic philosophy is not merely of historical value, but also conceptual and applicable. Its relevance becomes especially evident amid the crises of meaning, identity, and life purpose experienced by many modern students.

Moreover, Islamic philosophy offers an integrative paradigm of knowledge as an alternative to reductionistic approaches and serves as a response to moral relativism and the fragmentation of knowledge. Concepts such as being, the reality of existence, the gradation of existence, the perfection of the soul, and God as the pinnacle of perfection remain relevant frameworks for understanding reality and human existence in the modern era.

Adlany also explained that the ideas of major Islamic philosophers can be practically applied in students’ intellectual lives. Ibnu Sina, for example, emphasized systematic rationality and intellectual discipline. His thought encourages students to construct coherent and methodological arguments, which remain relevant for the development of academic reasoning and scientific thinking structures.

Meanwhile, Suhrawardi taught that knowledge is not merely conceptual but also a presence of meaning (‘ilm al-ḥuḍūrī). His approach encourages inner reflection, intellectual intuition, purity of the soul, and ethical sensitivity, helping students balance logic with self-awareness.

As for Mulla Sadra, he offered a synthesis of reason, revelation, and spiritual experience. His concept of substantial motion (ḥarakah jawhariyyah) teaches that learning is a process of existential transformation rather than mere accumulation of information.

Regarding the limited interest of students in Islamic philosophy, Adlany identified several contributing factors, including teaching approaches that are overly historical and textual, the use of technical language without adequate contextualization, and the perception that philosophy contradicts religion or lacks practical value.

He also noted that students’ pragmatism and materialistic orientation—viewing education primarily as a means to secure employment—pose additional challenges, given that Islamic philosophy is initially theoretical and abstract in nature.

As a strategy, he suggested linking Islamic philosophy to contemporary issues such as science, technology, ethics, artificial intelligence (AI), and the crisis of meaning. A problem-based learning approach is considered more effective than merely presenting a chronological history of philosophers. Islamic philosophy, he asserted, must be presented as a tool for thinking, not as a museum of ideas.

In the context of teaching, Adlany emphasized that Islamic philosophy should be taught as an exercise in thinking rather than memorization of definitions. It must be presented as a dialogue between texts, reality, and students’ lived experiences, and placed within an existential reflection on who human beings are, what the purpose of life is, and how life ought to be lived.

Approaches such as thematic discussions, reflective writing, and the integration of rational inquiry with ethical-spiritual dimensions are considered more effective in revitalizing Islamic philosophy in the classroom.

Finally, Adlany affirmed that within the tradition of Islamic philosophy, freedom of thought is part of intellectual responsibility. Reason is not positioned as a threat to religion but as a means to understand revelation more deeply and to distinguish reflective faith from blind imitation (taqlid).

“The tradition of Islamic philosophy shows that freedom of thought is not identical with relativism,” he stated.

With sound rationality, faith can grow into a more conscious and responsible commitment. Therefore, according to Adlany, Islamic philosophy can serve as a safe academic space for students to think freely without losing their religious commitment.