Between Meaning and Emptiness: The Tragedy of an Academic’s Suicide

A profound reflection on the suicide tragedy of an academic at Universitas Negeri Makassar, framed through the lens of philosophy, existential psychology, and the dynamics of academic life.

VOICES FROM THE EAST

Sitti Nurliani Khanazahrah, M.Ag. (Founder of House of Philosophical Studies, Makassar & Lecturer at UIN Alauddin Makassar)

7/23/2025

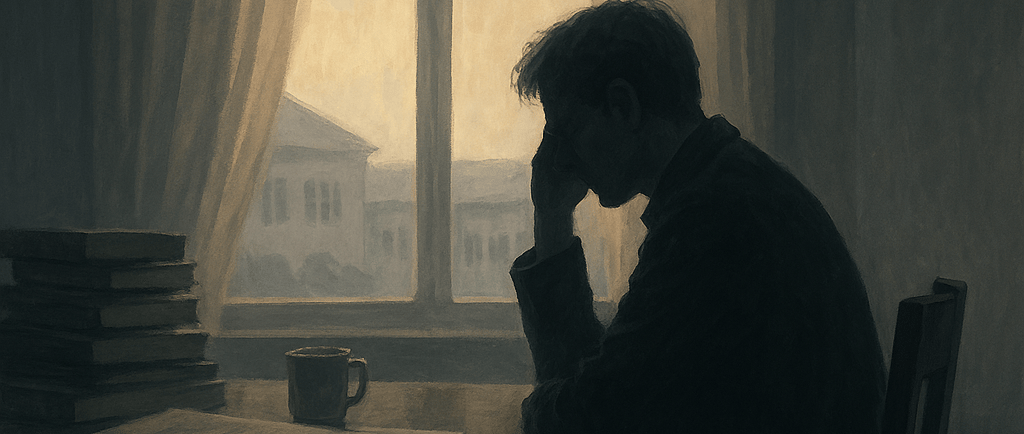

It was a truly silent morning—when news of death no longer comes from traffic accidents, hospital queues, or natural disasters, but from within the walls of academia. A place that is supposed to be a sanctuary of knowledge and life.

Some time ago, on Friday, July 11, 2025, a lecturer at Universitas Negeri Makassar ended his life in a shocking way. He hanged himself, leaving behind a legacy of unanswered questions lingering in many minds. Why would someone who appeared so educated, so secure in his career, choose to leave in such a tragic manner?

In truth, suicide among academics is not a new phenomenon, although it is often cloaked in silence. Behind the robes, journal articles, and academic titles lies a human life that is not immune to loneliness, anxiety, and existential fatigue. Those who spend their days discussing theories and methodologies can also lose their grip on life itself.

Albert Camus (1913–1960), a French philosopher, once wrote that suicide is the only truly serious philosophical problem. For him, the question of whether life is worth living is the fundamental one. Camus described the world as “absurd”—when humans seek meaning in a world that seems to offer no definitive answers. So what can we do? Is surrender the only option?

But Camus didn’t stop at absurdity. He offered rebellion—not a physical uprising, but the courage to continue living and to love life, even without certainty. It is a kind of inner resilience to keep moving in the midst of a void of meaning. Perhaps this is what many people overlook: that to endure, we must have the courage to embrace absurdity rather than fight it.

Yet such courage does not grow easily—especially when we live in an academic world that demands more and more. In the past, an academic was respected for their knowledge and dedication to teaching and research. Today, new pressures arise—less visible but no less suffocating. There are unspoken expectations: to dress elegantly, own the latest gadgets, drive a vehicle that reflects a certain social class, and so on.

A friend of mine, also a young lecturer, once joked, “If my laptop is outdated, students won’t respect me. If my clothes are too plain, I won’t look authoritative.” Behind the joke, I sensed his unease. Maybe it’s true—academia is gradually shifting from a space of truth-seeking to a stage for performance.

It's no longer about how deeply one thinks, but how well one presents. Fashion becomes a status symbol, gadgets a sign of prestige, and vehicles a marker of social rank. It’s no surprise many young academics are caught in this current, racing to project success even when their inner selves are exhausted and gasping for air.

Unfortunately, intellectual capacity, no matter how great, does not always equate to spiritual resilience. A professor or doctoral title doesn’t make one immune to feelings of emptiness. In fact, academic burdens and social expectations can increase one’s loneliness. Amid hard-earned achievements, some forget to build an inner sanctuary to rest their soul.

The question then arises: can we find meaning and true happiness within the campus environment? Can the university be a space for contemplation, not just a site for producing knowledge?

Throughout the history of philosophy, many have believed that true happiness does not depend on what we possess, but on how we live our lives. Epicurus (341–270 BCE), a philosopher from Ancient Greece, taught that happiness lies in tranquility of the soul (ataraxia) and freedom from pain (aponia). He rejected the notion that wealth and luxury are sources of happiness. Instead, he advocated for a simple life, friendship, and reflection as paths to joy.

In the context of academia, Epicurean principles remind us that academic life doesn’t have to be glamorous. Happiness can be found in honest conversations with students, in writings born from reflection, or in quiet hours spent in the library.

Regarding suicide, Ibn Sina (980–1037) wrote in his book Al-Najat that a healthy soul is one that knows its intellect and unites with the essence of being. He suggested that the soul’s suffering often stems from alienation—from oneself, one’s intellect, and from the Divine. In this light, suicide is not just a physical act but a sign that someone has lost their metaphysical orientation—forgotten to recognize themselves in the spiritual mirror.

On the other hand, Al-Ghazali (1058–1111) reminded us that true happiness lies in closeness to God—not through wealth or titles, but through purification of the soul. According to him, those who chase only the external world will always feel empty because they are estranged from their inner essence. This may be a reflection worth considering for academics: that writing journals and chasing research grants will never fill the soul if done without awareness of a higher purpose.

Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855), the Danish existentialist philosopher, spoke of despair as a deadly sickness. Despair, he said, occurs when someone refuses to be themselves. They are not at peace with their existence and do not accept themselves as they were created. In academia, this might be seen in those who feel like failures for not meeting institutional standards. Yet perhaps what is needed is the courage to accept oneself and walk a different, more authentic path.

To me, all these thoughts point to a single realization: that happiness is not the result of external accomplishments, but rather the outcome of self-recognition and acceptance. The university should be a place that nurtures this awareness—not merely a field for credit points, but a garden of the soul where people learn to become human.

In today’s world, perhaps we need to redefine happiness. Not as the accumulation of achievements, but as intimacy with oneself. As the courage to live slowly, to walk with the current without drowning. As the strength to continue teaching with heart, researching with love, and guiding with empathy.

This writing certainly cannot answer all questions about suicide. But at the very least, it can serve as a small space to begin asking more honestly: Does our campus still provide room for the soul to grow? Do we still allow sadness to be present, without rushing to cover it up with image-making? Are we brave enough to ask ourselves: what makes a life worth living?

Perhaps the answer is simple. It doesn’t lie in international seminars or certifications—but in the quiet moments when we dialogue with ourselves, and realize that we still want to live. Not because the world is perfect, but because we choose to embrace its imperfections with love. And from that point, perhaps life begins to regain its meaning—even if it’s as thin as the morning light peeking through the curtains of a silent campus window.